Wargaming the Neolithic

Can We Approach Prehistory as an "Historical" Gaming Period?

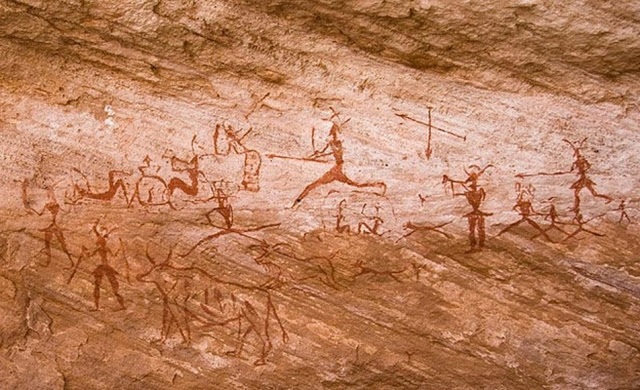

Rock paintings in the Tadrart Acacus region of Libya dated from 12,000 BC to 100 AD. Credit: WikiCommons

Rock paintings in the Tadrart Acacus region of Libya dated from 12,000 BC to 100 AD. Credit: WikiCommons

By Arofan Gregory, copyright (c) 2025. All rights reserved.

When we play historical miniatures wargames, we often face things that we don't really know about the period we are supposedly recreating on the tabletop - things where the best we can do is make an informed guess. For some, the degree of realism in a wargame is unimportant, so long as the game captures some type of "period flavor," which often means the same degree of historical accuracy we find in Hollywood movies (that is to say, only superficial aspects). For many of us, however, realism is what sets historical gaming apart from fantasy: we want to reproduce the warfare of the era as faithfully as possible because we are students of history. We want to fill the shoes of historical commanders, and to know what it was like to be there at the battles we read about in history books.

Even relatively recent history has its unanswered questions, but as we go back further into history, we find that these blank spots grow larger and larger. We do not, for instance, have very accurate data concerning the effectiveness of Napoleonic musketry, nor even that of the American Civil War: both are topics which spawn countless debates, but which can have a direct bearing on the way in which a set of wargames rules are designed, and the way our miniature armies function on the tabletop. And these conflicts happened in the recent, well-documented past! When we go back to the "Ancients" period, we begin to find really large gaps in our knowledge. No one can say with certainty how Hannibal, for example, managed to find elephants for his battles toward the end of his long campaign in Italy, after all the ones he brought over the Alps were dead, and yet we find mention of them in our most reliable sources. Was he reenforced from Africa? From Spain? There are obvious gaps in the historical record. We don't actually know how his armies were organized or who was in them with any great degree of accuracy, much less the specifics of how they were armed and fought. We only have informed guesses for much of this, but we are so used to assuming that the overall consensus is true (as codified in army lists) that we accept it as fact.

Archaeologists and historians - as with many academics - like to speak about their fields of expertise with great certainty, but I would argue that this degree of confidence is not always warranted. If you follow the evolution of academic thought, today's certainty will inevitably give way to tomorrow's, and this pattern will repeat endlessly over time. It is clear that ancient history, especially, is imperfect, no matter how confident the proponents of any given theory are.

Unlike historians, miniatures wargamers cannot simply say "I don't know" when faced with a question which is difficult to answer: in order to reproduce something on the tabletop, you must often decide what you think is most probable, even in the face of very slight evidence. I would argue, however, that - like living history - wargaming sometimes provides insights which the traditional academics miss. As an example I remember reading an academic account of Middle Eastern chariot warfare, in which it was stated that light, two-horse chariots might have been missile platforms, but that they might also have been intended for close combat, and that there was no evidence either way. This is laughable - as any ancients wargamer could tell you, a light, two-horse chariot is by its nature designed as a missile platform. It may be used for scouting or transport, too, but it is not intended to be used for charging into close combat, a role for which it is pathetically unsuited. Living history experiments with recreations of ancient British chariots bear this out: the side rails which seem decorative were actually intended for an archer to brace their legs against while shooting from a moving chariot. The riders would dismount to fight on foot when it came time for close combat (we know this from the written record.) Similarities of design between ancient British and Middle-Eastern chariots don't leave a lot of room for doubt.

Even so. we must accept that we are almost always operating on informed guesses and theory. There is a huge amount which we don't know, and - even as the academic research advances - we will probably always be doing so to a large extent.

So, given all of the uncertainty around ancient combat, why do we bother? The answer is simple: ancient history is perhaps even more enticing exactly because it is unknown: we can read Gilgamesh and then raise the armies of Akkad and Sumer to clash on the tabletop, fascinated by what people were doing at the dawn of history. The very process of researching and buying the armies, painting them as accurately as possible, building appropriate terrain, and then leading them into combat exposes us to a huge amount of information we would otherwise never have bothered to find. It is learning for its own sake, and it is incredibly satisfying, even if some of what we are doing is based on informed guesswork.

And this is exactly why it makes sense to push even further into the past, into the realm of prehistory.

A shaman and the tribal chief try to overawe their enemies.

When we decide to look into prehistory as the subject of a wargame, we are immediately presented with a huge question: "At what point did organized warfare come into existence?" I am no expert, but I think the consensus view seems to be that organized warfare really started with the later Stone Age - the Neolithic. There was an event in human societies which is termed the Neolithic Revolution, around 6500 BC (although this varies by a wide margin based on where in the world you are talking about), when agriculture and animal husbandry became widespread, and nomadic hunter-gatherers became sedentary. This event coincides with the first evidence of organized warfare, which makes sense: when your home (which is your source of food) can't move, you will stand your ground and defend it. Likewise, it offers an easily located target for those who think they can profit from the efforts of others through violent means.

By this logic, it could be surmised that any static settlement would produce the conditions for warfare. As we will see below, sites like Lepenski Vir in Serbia pre-date the Neolithic, having been constantly occupied from the Mesolithic era. There would not only have been farming, here, but - perhaps more importantly for earlier settlers - consistent access to the Danube, a source of fish. Other such static settlements might occur in places where the stone needed for tools was available (see the description of Hamoukar, below). Even religious sites such as caves or stone circles might meet this criteria. It would seem that the real drivers for warfare - like the drivers for the development of agriculture itself - are population pressure and access to sufficient resources. An agricultural lifestyle is conducive to this combination, allowing for rapid population growth and static targets for raids, but is not the only reason it occurs.

We should note that the Neolithic is well after the end of the last ice age - the mastodon and the saber-toothed tiger are, by this point, extinct. (Also - no dinosaurs. Really, I mean it - no dinosaurs!) People are modern humans - Homo sapiens - not Neanderthals (Cro-Magnons are technically modern humans, Homo sapiens, having died out only around 10,000 years ago.)

(As an aside, when we are dealing with the Stone Age, we have to be careful about dates. The "Old" Stone Age - the Paleolithic - was followed by the "Middle" Stone Age - the Mesolithic - which was followed by the "New" Stone Age - the Neolithic. This in turn was followed by the Chalcolithic (Copper Age) which was followed by the Bronze Age. These designations are not bounded by hard dates. They are descriptors of human culture's development in various parts of the world. Thus, we see the Neolithic is later in northern Europe than in the Balkans or the Near East, for example.)

Overall, we do not have a lot to go on here: there are a number of sites in Europe which have been excavated, and some in other parts of the world. (A few of these are summarized below.) We can be certain that there was organized warfare during the Neolithic, however.

Before this time, there are some intriguing possibilities: in Mesolithic cave paintings in Spain, we find depictions of people shooting at each other with bows, and in some cases - notably in Sudan and Kenya - we have very old evidence of massacres which could be related to warfare. However, the scientific evidence is apparently not conclusive in these cases. It is not that people weren't fighting before the Neolithic - they clearly were. But organized warfare is defined as something more than a violent confrontation between members of the same group - it requires a clash between two different groups or societies, and this is somewhat harder to prove.

Another question we probably want answered is "Why did they fight?" Wars have been fought for some pretty silly reasons over the years, granted, but it still helps to understand what these early people considered to be worth fighting over. Some of the answers will seem obvious: territory, women, cattle, and slaves. Others are perhaps more surprising: cannibalism and human sacrifice! Regardless, understanding the motivations for the earliest organized warfare is necessary if we are to write good scenarios for our games.

A third question is "How did they fight?". This last question is more easily answered by reference to the archaeological record.

Here are some examples of excavated sites and finds which provide answers to these questions, and possibly raise some other ones:

(1) Talheim Death Pit, Talheim, Germany, 5000 BC. Remains of 34 individuals were found, said to be evidence of warfare among similar, competing settlements in the area. Of 34 individuals, most were killed with axes (adzes) but 2-3 were killed with arrows. The majority of skeletons were adult men, with a marked absence of women. Healed wounds from weapons indicate that this was not a one-off massacre, but that fighting was ongoing over time. Reasons for the conflict are theorized as land, women, resources, poaching, dominance, and slaves.

(2) Massacre of Schletz, Asparn an der Zaya, Austria, 5000 BC. Two hundred people, mostly killed using stone axes (one from an arrow), were buried in a mass grave outside a fortified settlement. Many of the heads had been separated from their bodies, and many were missing arms and legs. There were hardly any young women. After the burial, the settlement was no longer inhabited, so it seems that the occupants of the grave may have been residents of the village. Motives again would include women and slaves.

(3) Massacre at Schöneck-Kilianstädten, Germany, 5270-4849 BC. Another mass grave site, featuring a very high number of broken "long bones" (especially in the leg). These are taken to indicate deliberate torture or mutilation of victims, as they occurred at the time of death (but were likely not the cause of it).

(4) Mass Burial at Herxheim, Germany, 5000 BC. This is another mass grave with a pattern of killing featuring beheadings. This is an enclosed site, but is thought to be a religious center rather than a fortified village. The scattered remains of 1000 people, some from distant areas as much as 300 miles away, show evidence of having been roasted and consumed by humans. This suggests that people were being captured not only for forced labor but for human sacrifice and as a food source. Human remains - especially skulls - were turned into ornaments. These guys show every sign of being a death cult!

(5) Hamoukar, Syria, 4500 BC. This was the site of an urban center which was a major obsidian producer. It came to a violent end at around 3500 BC (that is during the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, not the Neolithic) but there were slings and lots of clay sling stones found at the site. It is surmised that the fall was the result of an attack by Uruk.

(6) Ötzi the Iceman, Ötztal Alps, Border of Italy and Austria, 3350 - 3105 BC. This is the famous frozen corpse who died of an arrow lodged in his scapula. He had the blood of four other individuals on him, and it is thought that he killed one enemy with his knife, two enemies with a single arrow, still in his quiver, and had carried a third wounded man (presumably a friendly) who bled onto his clothes. The shaft of the arrow that killed him was removed before he died. He carried a stone knife and arrows, a yew longbow, and a copper-headed axe. The axe head was cast, with the copper coming from southern Tuscany, some 400 miles away. The condition of his joints indicates that he spent much of his life traveling on foot, although genetic evidence indicates that he came from a race of sedentary farmers.

(7) Amnya Complex, Siberia, 6100-6500 BC. This is a set of two fortified complexes, each of 10 pit houses, representing one of the earliest known example of fortification. (The sites had been occupied from the Mesolithic, but the fortifications weren't built until afer 6100 BC). This was a settlement of proto-Indo-Europeans practicing agriculture and herding. They were also active hunters and warriors, as attested by the artefacts found at the site. The pit houses showed evidence of often being burned, presumably in raids.

Another site which is very intriguing although not directly related to warfare of the era is Lepenski Vir, on the Danube in Serbia. Here, a number of trapezoidal houses were built around a bend in the Danube, and embedded in the floor were statues of what are termed "fish-people". There were several villages strung out along the Danube, progressively established as the population seemed to out-grow available resources in the constricted areas between the mountains and the river. Further, in addition to the villages a necropolis was discovered. The site was occupied from the early Mesolithic through the Neolithic. (While extremely fascinating in its own right, this is also really good fodder for somebody who wants to build scenarios with an imaginative religious element. You will notice that I did not use the words "Cthulu" or "Lovecraft" anywhere in that sentence... I am trying to be "historical" here!)

Other sites also show that often animals have great importance - as food, certainly, but also as symbols of power, fertility, etc., and possibly even as gods. Bear cults are known to have existed in several places, for example, possibly as far back as the Paleolithic (although this is much disputed). The existence of bear cults in many cultures at later times is well attested however, and this may have included the Neolithic. There is evidence of many other animals being viewed as religious symbols, including snakes, bulls, deer, cranes, dogs, owls, boars, toads, turtles, and even hedgehogs. Certainly animals which served as food, both as prey and domesticated, were treated with reverence and were the focus of rituals, as we see in cave paintings and archaeological sites in Italy, Iberia, Germany, the Balkans, Africa, and elsewhere.

While wild and - later - domesticated horses were a food source, it is not clear whether Neolithic people rode horses. There is a theory that late Neolithic cultures in the Balkans were taken over by Indo-European mounted raiders from the steppes, so including them in a game is conceivable, although some would maintain that the horses were used for carts and chariots rather than as mounts for riders. If you are curious it is worth researching the "Kurgan Hypothesis" (horsemanship may more properly belong to the Copper Age, or even later).

It doesn't seem to be working!

So, it is clear that we do not know a lot about the warfare of the Neolithic, but we do have some hints as to what occurred. We know that weapons would have included spears, knives, axes, adzes, clubs, bows, throwers for darts/javelins, boomerangs, slings, and thrown rocks. It seems likely that deaths were not primarily from missile weapons however, but were more often inflicted with close-combat weapons, if the occupants of mass graves are a reliable indicator (which many would claim they are not, to be sure). Thus, our Neolithic war parties should have some missiles, but a higher proportion of spears and axes. Although not found at the sites described above, the first shields are thought to have been developed during the late Neolithic period.

It should be noted that there is no evidence for the use of dogs in war prior to the Bronze Age. However, this is still something which might seem to be likely, given that dogs were used for hunting (9000 BC) and herding (6000 BC) during this period.

It is clear that Neolithic people could travel fairly long distances, including probably for the purposes of warfare. We see this in the case of Ötzi, but also in the remains at the mass burial in Herxheim. There is evidence that some form of trade was carried out over significant distances. As the Neolithic gave way to the Chalcolithic, we do know that long-range trade networks became established.

The motives for warfare clearly include not just defeating the enemy, but capturing them for various purposes. This would include not only women, but also children and adults for use as slaves or for human sacrifice, consumption, or both. Consider that many societies have performed human sacrifice well into the historical period, including not only the Meso-Americans most famous for it, but also the Shang Dynasty Chinese, the Celts, and even the Romans during the Second Punic War. There are also many examples of primitive cannibalistic hunter-gatherer societies such as the Tupi in the Amazon, the headhunters of New Guinea, and so on. It is easy to understand that this was an important aspect of warfare during the period, and we do have archaeological evidence to back it up.

Another motivation would be the seizure of domestic animals, and in some cases mineral resources such as obsidian or flint and presumably copper. Real estate in a desirable location might also be a target, although this is a supposition on my part - it is certainly the case that we see examples of successful populations growing too large for the resources of the area they have settled in, as at Lepenski Vir.

We can only speculate about the specifics of religion, but it is fair to assume that superstitions of various types were extremely common, and that shamans, witches, priests, and priestesses would be credited with the performance of magic. Animals were very important, as were weather and fertility. The importance of omens and portents is likely, given how significant these were right up through the Classical Era and even the Dark Ages (and beyond, in some cultures). Megalithic structures such as Stonehenge also cry out for inclusion in a game, and appear in various forms throughout the world. It is clear that the forces of nature and the supernatural were given a huge importance by these societies, even if we have only a few clues to tell us what their ideas about these were. We can assume that superstition was rife - remember that as late as the 17th Century witchcraft was taken very seriously as a matter for government policy in European cultures, which is very recent in historical terms! (As a modern American I can attest to the fact that people still use fear and ignorance as the basis of legislation: chem trails!)

The shamans and priestess argue with the Tribal chief.

Populations were small in pre-history. The fortified village mentioned above at Schletz consisted of only a dozen long houses, and in other parts of northern Europe (and all over the world in most places) small settlements of 50-100 people are probably the norm. In the southeastern part of Europe there was a higher population density - but even so, the settlements at Lepenski Vir, a major urban site for the Balkans that included several villages, had only hundreds of inhabitants (136 buildings have been found, including religious ones). By the very end of the Neolithic, the largest urban centers of "Old Europe" in central Europe and the Balkans could have as many as 1500 buildings in them, housing 10,000 people or more, but most urban settlements would be much smaller, with 3-4000 people. Even given the fact that most (if not all) able-bodied men would have presumably become part of the military force of such groups, we are still looking primarily at fairly small skirmish-level conflicts in wargaming terms. Some estimates indicate that a typical war party would consist of 20-30 individuals.

Given the absence of any hint of tactics based on drill, it is probably safe to assume that warfare was focused on the efforts of individual warriors. That said, prehistory clearly gives us examples of hunters working in a coordinated fashion to trap herds of bison or mastadons, so these types of tactics would exist. What we probably shouldn't allow are close-order, formed bodies of troops.

Animal and plant life was not terribly unlike what we find in the wilderness of the modern era. Some things have disappeared - aurochs and wild horses (as opposed to escaped domesticated ones) had not yet gone extinct - but other animals such as wolves, bison, deer, and bears would be entirely familiar. The landscape would be covered in familiar plants, too, much like today. From this perspective, we may need to produce some new terrain for human settlements and so on, but we will not need to produce any giant ferns or anything!

It makes sense, then, that our wargames should reflect what we know or can surmise, emphasizing the motivations and considerations above. Which leads us to our next topic: rules.

Neolithic people fighting in a familiar landscape.

There are several sets of rules for the prehistoric era, although some of these are not for wargames per se, but rather rules for hunts, and tend to be set during the last ice age when people could still encounter mastodons and similar megafauna (i.e., "Tusk"). Some focus more on "Lost World" scenarios where more modern (e.g., Victorian or Pulp) adventurers encounter cavemen and dinosaurs. "Prehistoric Settlement" is more of a primitive version of Civilization or Empire - players try to build an entire prehistoric society, rather than just fighting a war. The "Tribal" rules can be used for prehistoric combat, although they are not period-specific - even the "Primeval" pre-history expansion covers everything from Neanderthals on. Some rules sets are decidedly more fantasy-oriented than historical ("Battles before Time", "Savage Core"). Still, that provides a degree of choice for the wargamer.

My own inclination, as an old-fashioned historical wargamer who likes to write my own rules, is to take a set of skirmish rules and modify them. In my case, I have settled on Ravenfeast as a likely candidate, albeit with modifications to address the need to incapacitate and capture enemies, rather than just kill them, and with the addition of more "magical" elements than just the use of "Rune Cards" (although this is a start). Also, such things as shield walls are given a miss as being non-period. If I had to choose a commercial set, I would go with "Tribal" - even though I am not fond of card-driven games (it uses poker decks instead of dice). A lot of thought has clearly gone into it.

Copplestone cavemen face off against Eureka's Denisovans.

The nice thing about all of these almost-but-not-quite wargame rules is that there are consequently lots of miniatures available, mostly in 28mm (as is appropriate for a skirmish game), but also in 15mm and even 6mm. The following list is probably not complete, but it at least gives you a place to start.

Copplestone "High Adventure: Lost Worlds" 28mm

Northstar Fantasy "Tribal" Cavemen 28mm

Steve Barber Prehistorical Settlement 28mm

Eureka Denisovans, Neanderthals 28mm

Reaper Miniatures' "Caveman Pack" and "Black Bear Tribe Cavemen" 28mm

Pulp figures "Lost Worlds and Lost Tribes" Neanderthals 28mm

Khurasan Miniatures Fantasy Cavemen 15mm (scroll down)

Given that we have only the most basic idea of how people dressed during this period, we can get away with almost any "caveman" figures. Depending on your taste, so you may wish to be picky: you will find that some are more of the "Raquel-Welch-in-a-fur-bikini" aesthetic than others.

For terrain, there are some items available from some of the vendors listed above, and in addition there is a useful (free) set of "fantasy" huts, pallisade, and camp items available to 3D print from Thingiverse. Another free file for 3D printing is a very basic straw hut of my own creation (as seen in the photo above). Other useful files from Thingiverse include the Celtic Round House and the OpenForge Tribal Hut. There are also some menhirs and stonehenge models - this one and this one are both good, but there are plenty of others. Being standing stones, they can be scaled to taste.

Reconstruction of a camp from 7,000 BC. (Photo by David Hawgood, CC BY-SA 2.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13976927)

The "Neolithic Bottleneck" is a phenomenon which has been spotted by people studying ancient human DNA. During the Neolithic, genetic studies indicate that there was only 1 breeding male for every 17 breeding females. Here is one explanation for this. There is also a short video made to explain the bottleneck. Apparently, the intensity of warfare in Europe, Asia, the near East and Africa was so bad that 95% of male genetic diversity was wiped out (not literally 95% of the population, but 95% of the different bloodlines). This makes the Thirty Years' War look like amateur hour! (Honestly, this is difficult to believe but it is what the current hypothesis asserts.)

A general explanation of prehistoric warfare can be found on YouTube: The Origins of Warfare (500,000 BC - 3,000 BC). This gives a good overall summary, and covers a lot of what I have written above in a bit more detail.

Another fascinating topic of study is "Old Europe," an advanced civilization in the lower Danube valley during the late Neolithic and Chalcolithic. Before the Mesopotamian civilizations, there is some evidence of a pre-Indo-European civilization here which was (according to some) wiped out by (mounted?) Indo-European invaders from the steppes. (There is an interesting and widely held theory about this called the "Kurgan Hypothesis"). This is a fascinating topic, and could make for some interesting games (although you might need to do a lot of figure conversions for this one if you decide that Indo-European horsemen are needed). Anything by Marija Gimbutas, the Lithuanian scholar who pioneered this research, is useful reading, although it tends to be very dry (it is academic writing). Other scholars have since developed her ideas further.

Bernard Cornwell is best known as the author of the Sharpe's Rifles novels, and he has done lots of other historical books which are popular with historical wargamers. One of his less-known efforts is Stonehenge, which is his novelization of life in Britain at the time when such megalithic structures were still a focus of society, at the dawn of the Bronze Age. For those of us who enjoy such things, this can be a good source of inspiration, as Cornwell may take liberties with his history, but he generally has done his research, and he spins a ripping yarn. Another favorite series is Michelle Paver's Chronicles of Ancient Darkness. Perhaps better known is Jean M. Auel's Earth's Children series. The Clan of the Cave Bear is the first one - also a movie, which has received mixed reviews. For other movies, there really don't seem to be a lot of good ones: 10,000 B.C. is not exactly a cinematic masterpiece, although both it and Alpha (the one from 2018) are fun if you are in the mood. And there's always One Million Years BC which at least has the excuse that it's a classic 60s flick (speaking of Raquel Welch in a fur bikini), although not even slightly realistic. (To be honest they all seem pretty challenged on that front.)

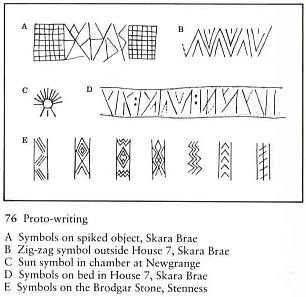

For learning more about what Neolithic structures looked like, it is fairly easy to find speculative reconstructions. There is a very nice grass hut model depicting the houses at Lepenski Vir, and there is a picture in the Wikipedia entry. Another interesting site is Skara Brae in Orkney, where a Neolithic village was buried under the sand for centuries before being uncovered. There is a 3D model of the site available online.

Symbols found on Neolithic sites in Britain. (Fantoman400 at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Another interesting site in Britain is Ness of Brodgar, a "city" dating back to 3500 BC. It is located in Orkney, in Scotland, and was built at the same time as the better-known city-states of Mesapotamia. The BBC did a documentary on it titled Britain’s Ancient Capital: Secrets of Orkney (Episode 1, Episode 2, Episode 3), arguing that from 3500 BC until the start of the Bronze Age, Orkney was the center of the first unified culture in Britain. (And some of the finds in the Orkney islands suggest that it was a very violent time.) Other sources suggest that the sedentary farming culture of Britain came from the Continent by way of Iberia, to where it had spread along the northern coast of the Mediterranean. These farmers supplanted the hunter-gatherer cultures already resident there. Overall, Stone Age Britain provides a rich set of possibilities for speculative wargames.

This is a fascinating era, with just enough information available to be tantalizing and spark the imagination. The idea of lost proto-civilizations, endless warring tribal factions, and clans of death-cult cannibals is very intriguing, and all of it is borne out by what little we know. If we are to engage in speculative "historical" gaming, then there does seem to be enough to work with and still retain some basis in the archaeological record.

It seems to me that we can reasonably go back at least as far as the Neolithic in our attempts to create historically plausible tabletop miniatures wargames. There is certainly a lot we don't know, but if this doesn't bother you too much, I don't see that this is massively different from fielding Ancients armies like the Sea Peoples, which are based almost entirely on speculation and a few Egyptian mosaics and wall inscriptions. We have useable rules and plenty of miniatures, so why can't we build on what we know of the evidence to at least try to represent the earliest warfare known to our species? Like any other period, it provides us with a diverting and fascinating way to study a new subject. (And at the very least, it lets us extend that pile of shame more than 2000 years into the past! What's not to like?)